Helpful hint:

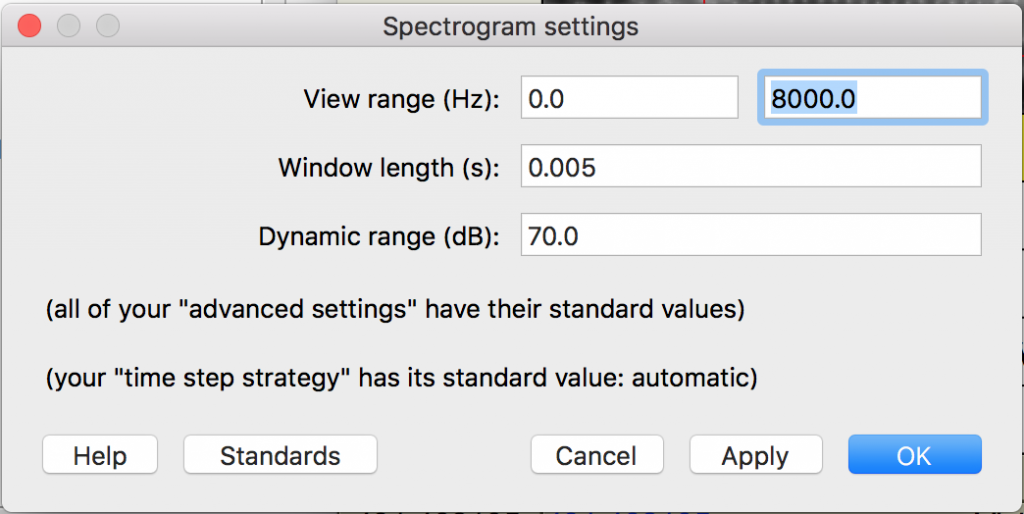

Set the spectrogram settings to 0.0 to 8000 Hz, so that you can see frication that is above the 5000 Hz default.

Also set the dynamic range to 70 dB instead of the default 50, which gives you greater detail in the z-axis of the spectrogram.

When hand correcting textgrids, here are some landmarks to look for:

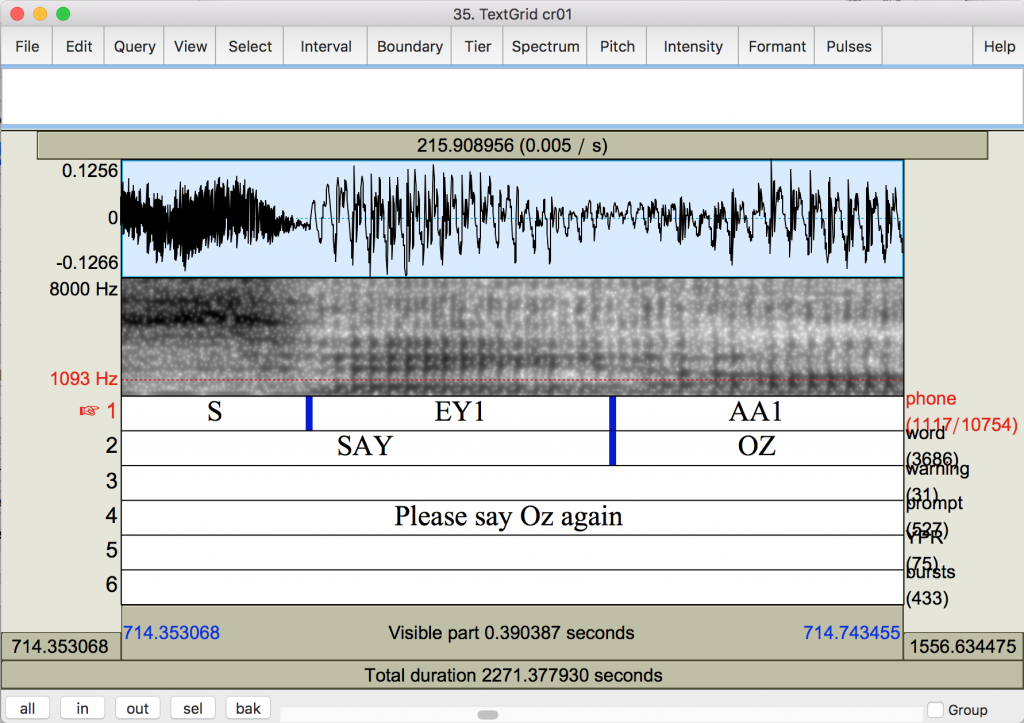

- Discontinuities (abrupt changes) in the spectrogram and/or waveform can be helpful in placing boundaries. Some phones are very different from each other. These boundaries are easy to identify by discontinuities in the spectrogram or waveform. Discontinuities are easier to spot if you are zoomed out to include about 4 or 5 phones in your window. Put your cursor where you think the change occurs, and then you can zoom in to see if you were right.

- Other sounds have lots of coarticulation between them, or are defined by being very dynamic (there is no/very little ‘steady state’), so you are looking for a moving target. These will be addressed individually.

Nasals:

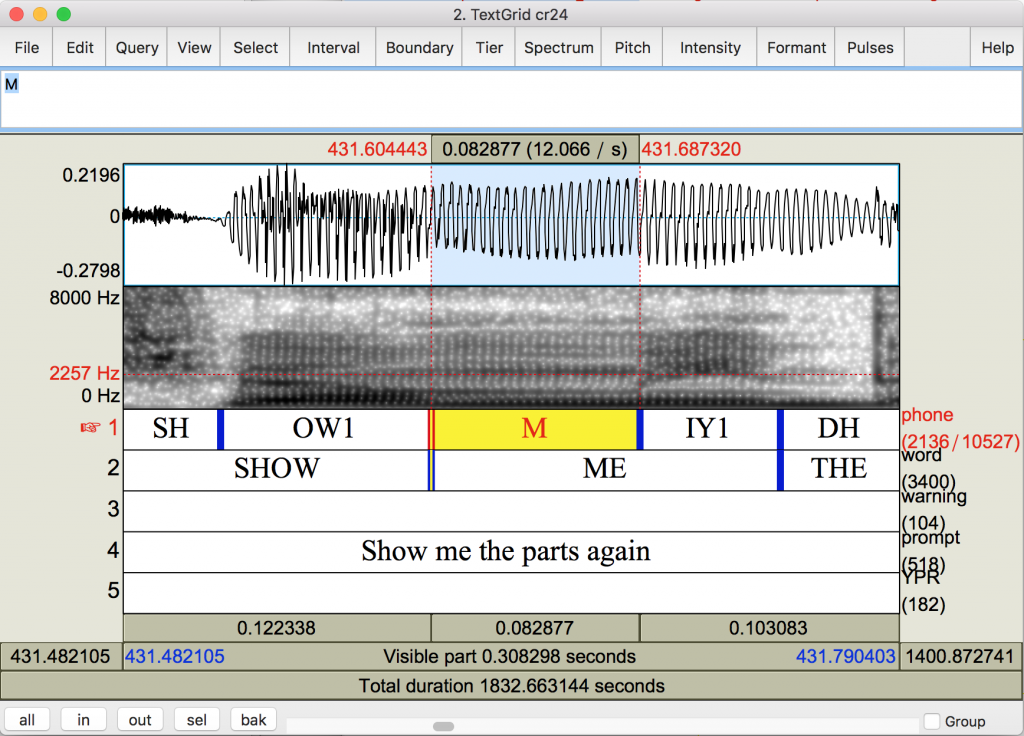

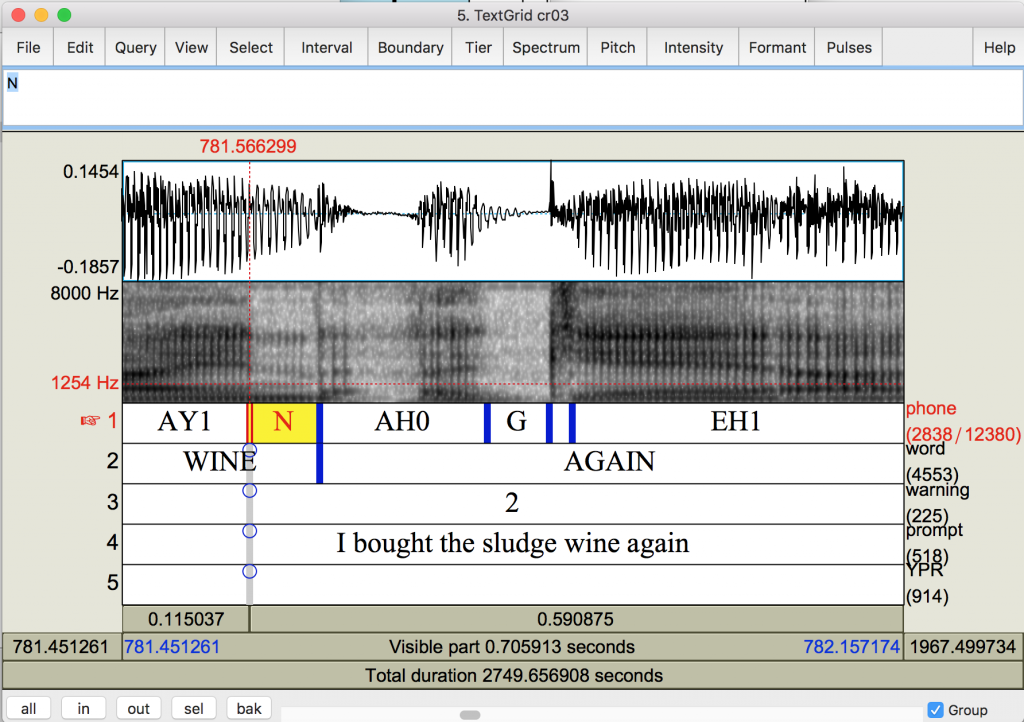

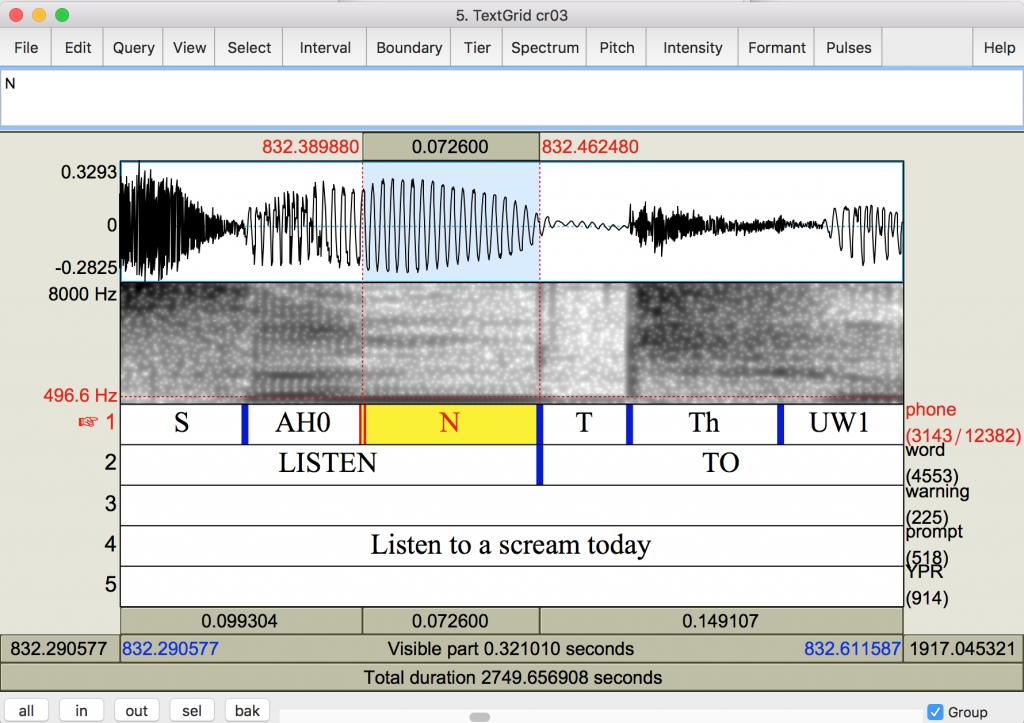

- Nasals are usually easy to identify because theu have a characteristically lower amplitude than surrounding vowels, and anti-resonances that damp some formant frequencies, resulting in a smoother waveform, and slightly lighter formants in the spectrogram:

- Sometimes the preceding vowel will be nasalized, making the boundary less clear. Just try to segment the actual nasal portion as its own phone, where possible. If it ends up being a syllabic nasal, do your best to make two segments out of it.

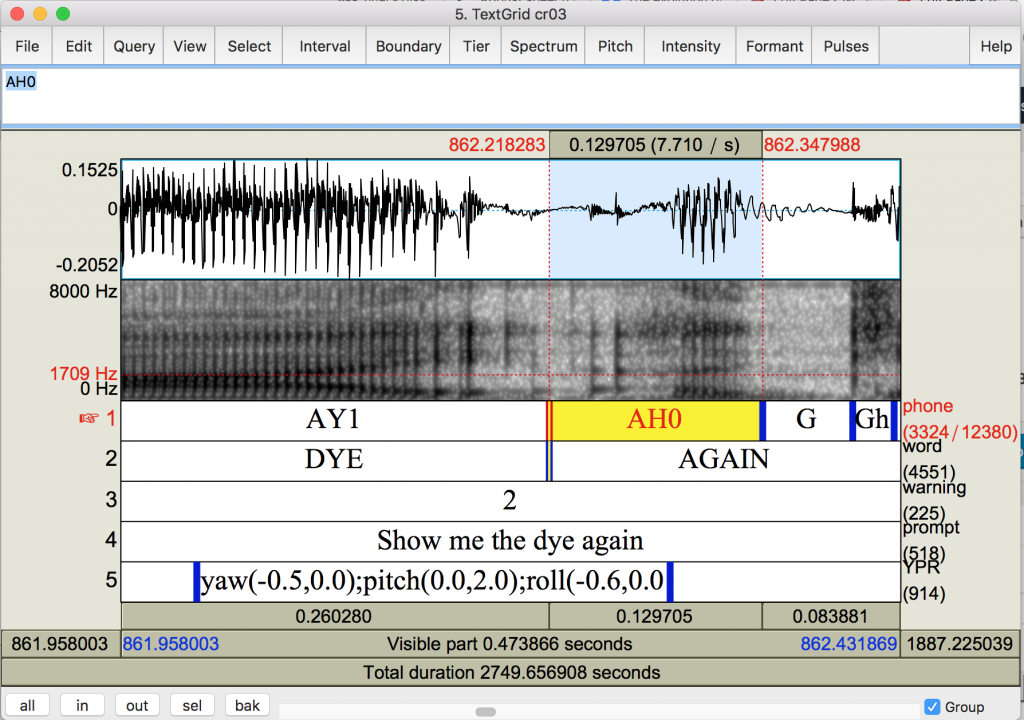

Stops and affricates

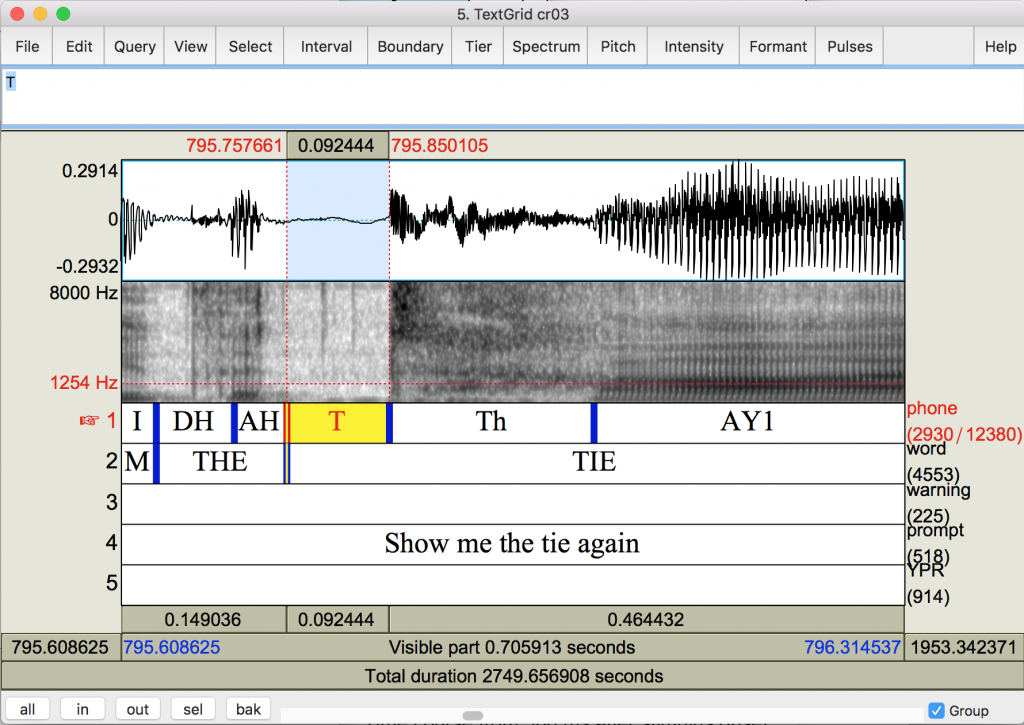

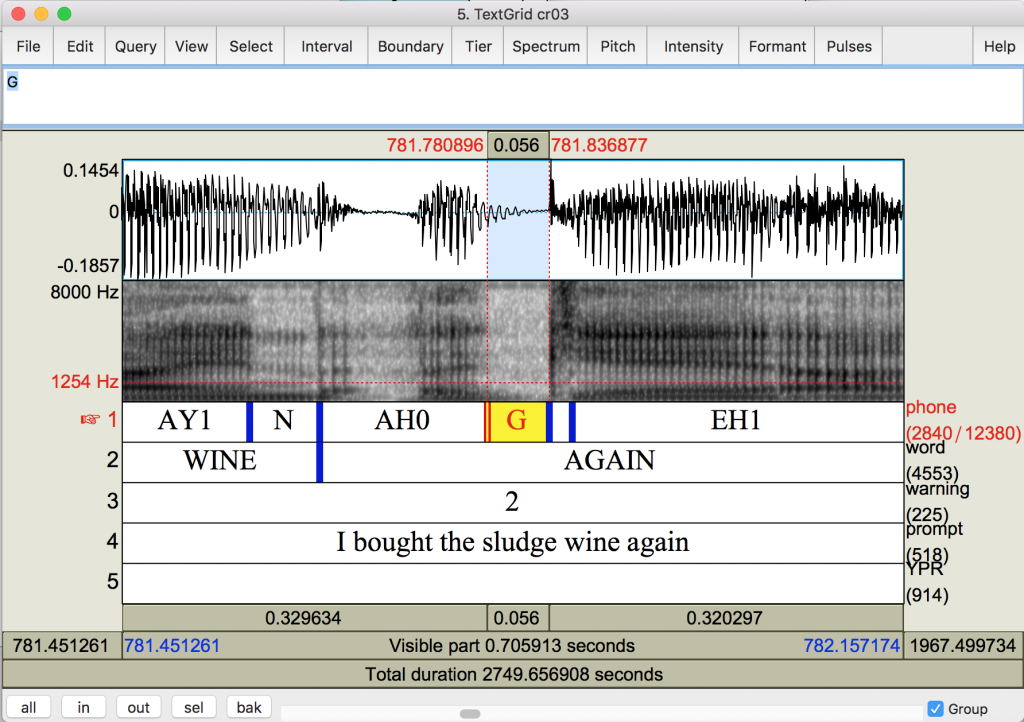

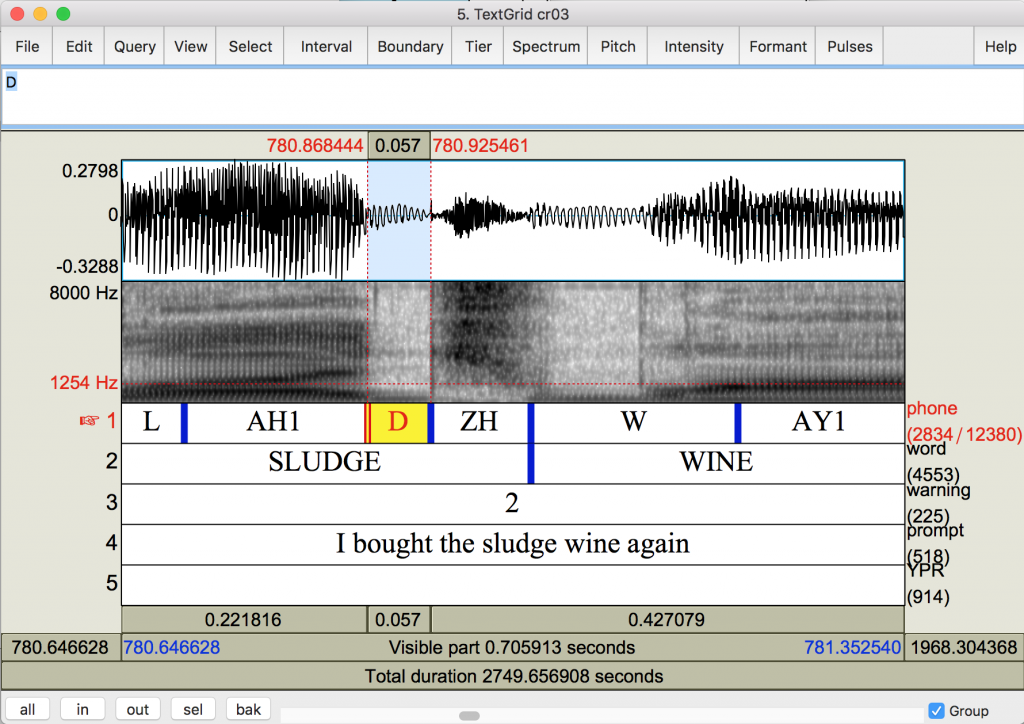

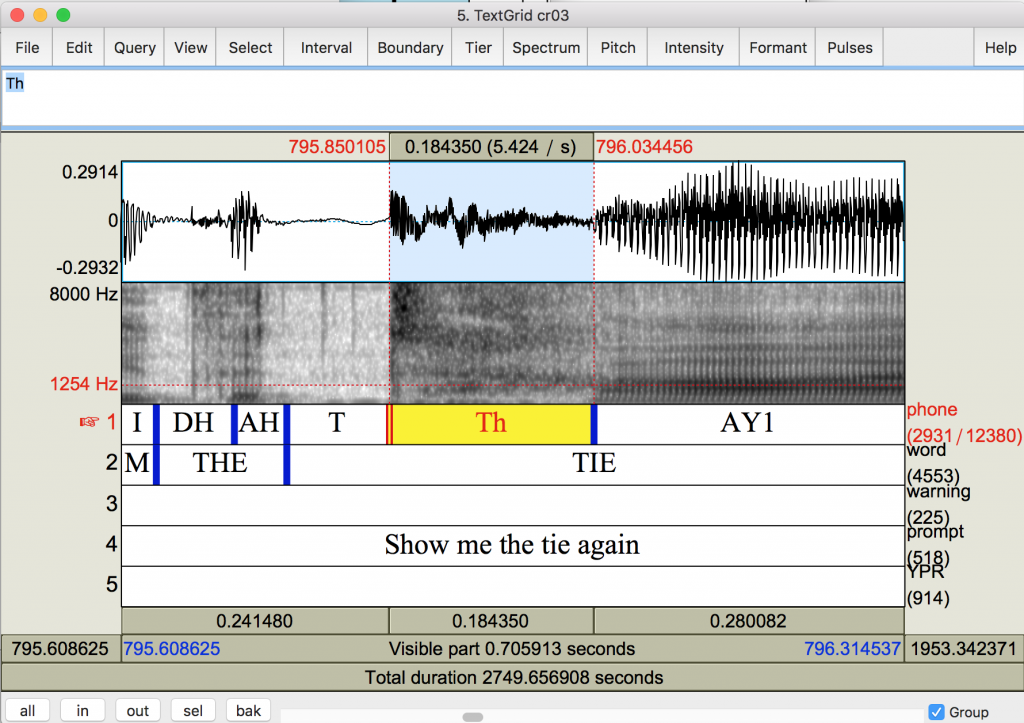

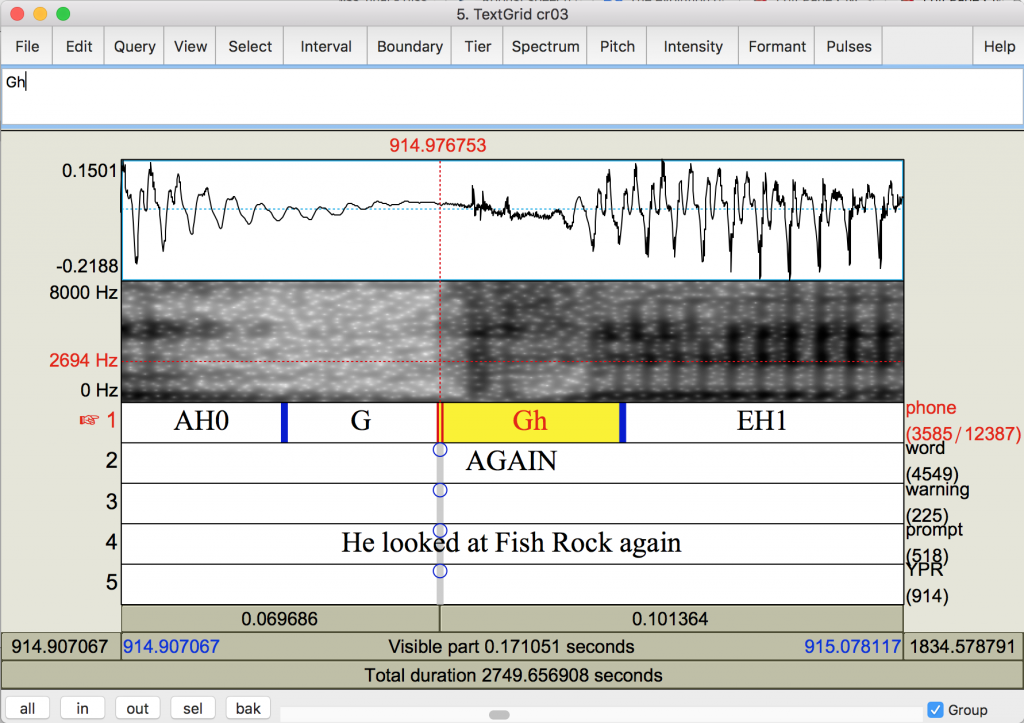

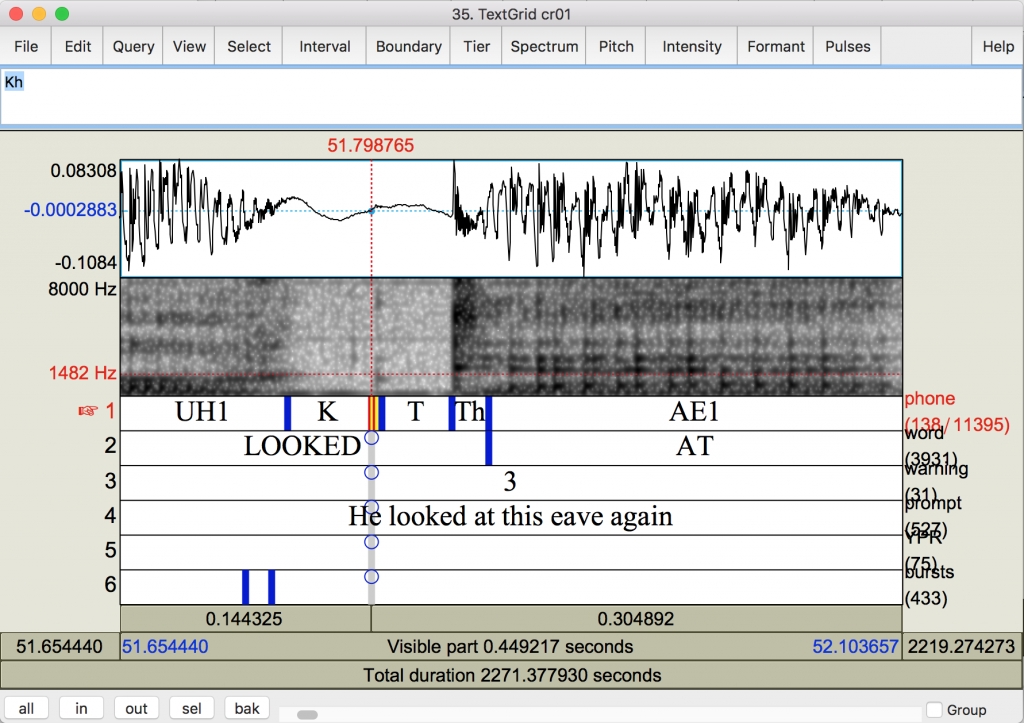

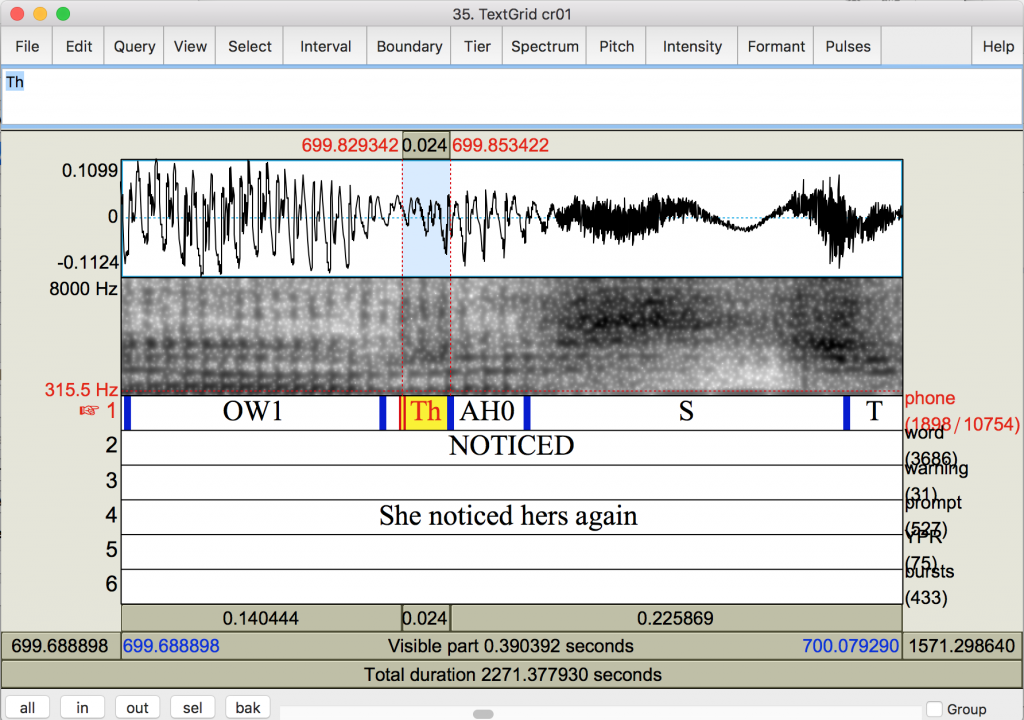

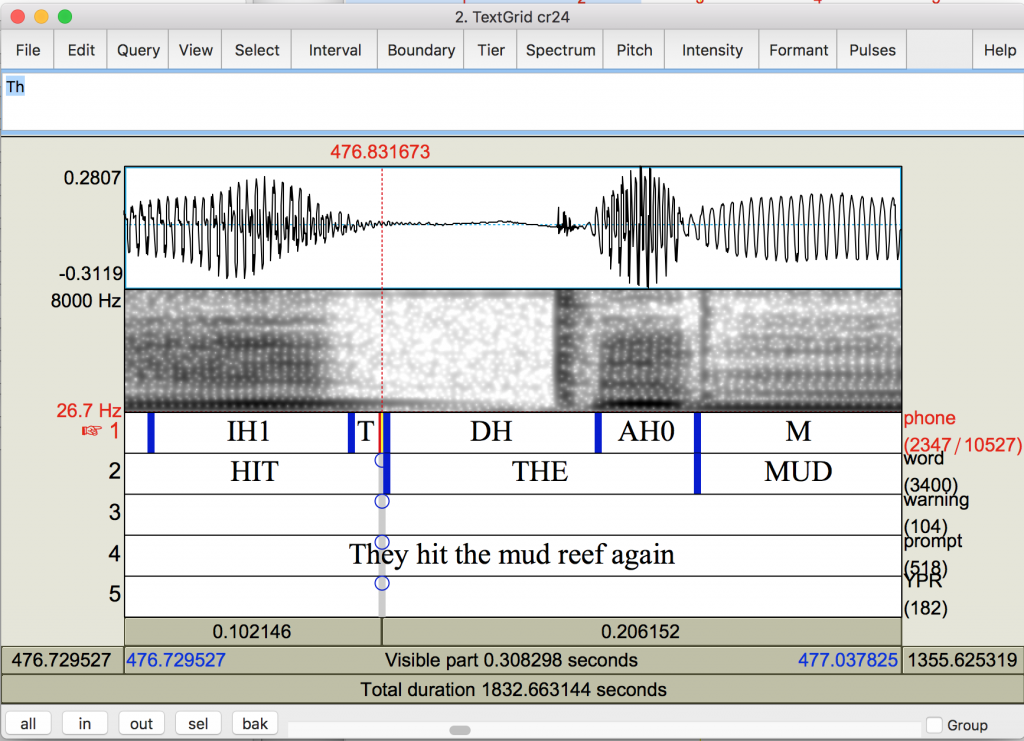

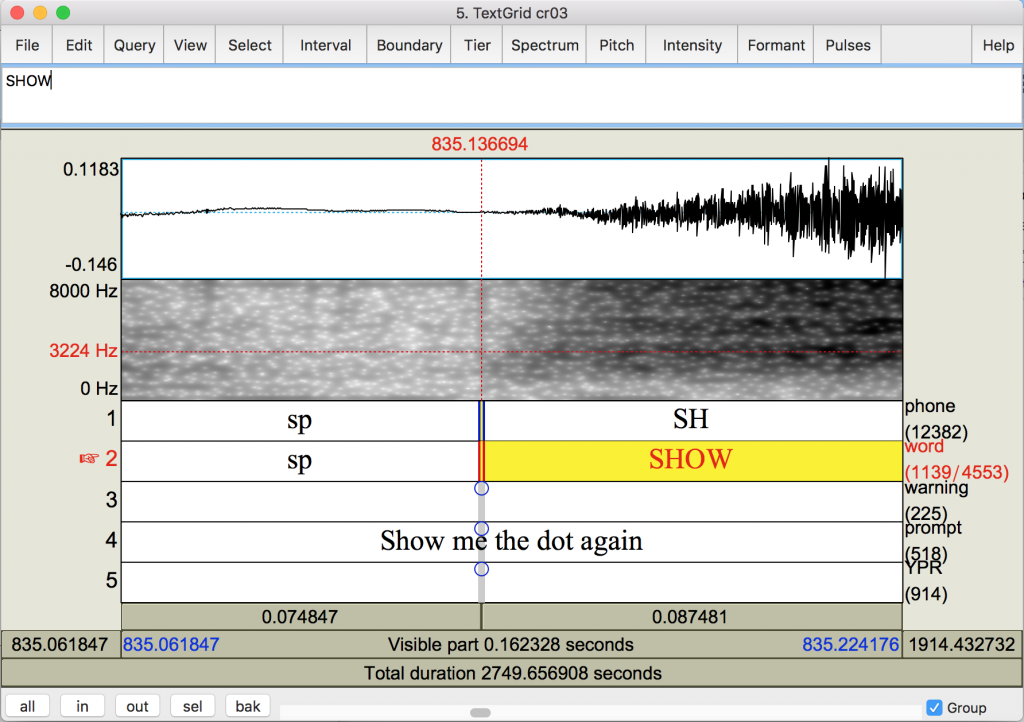

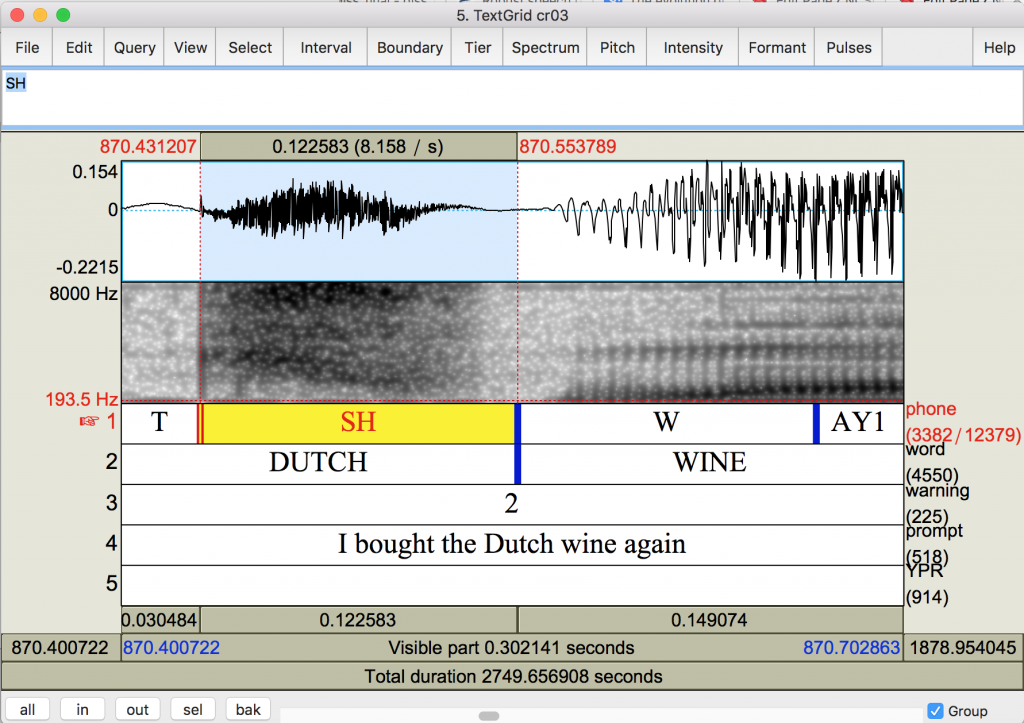

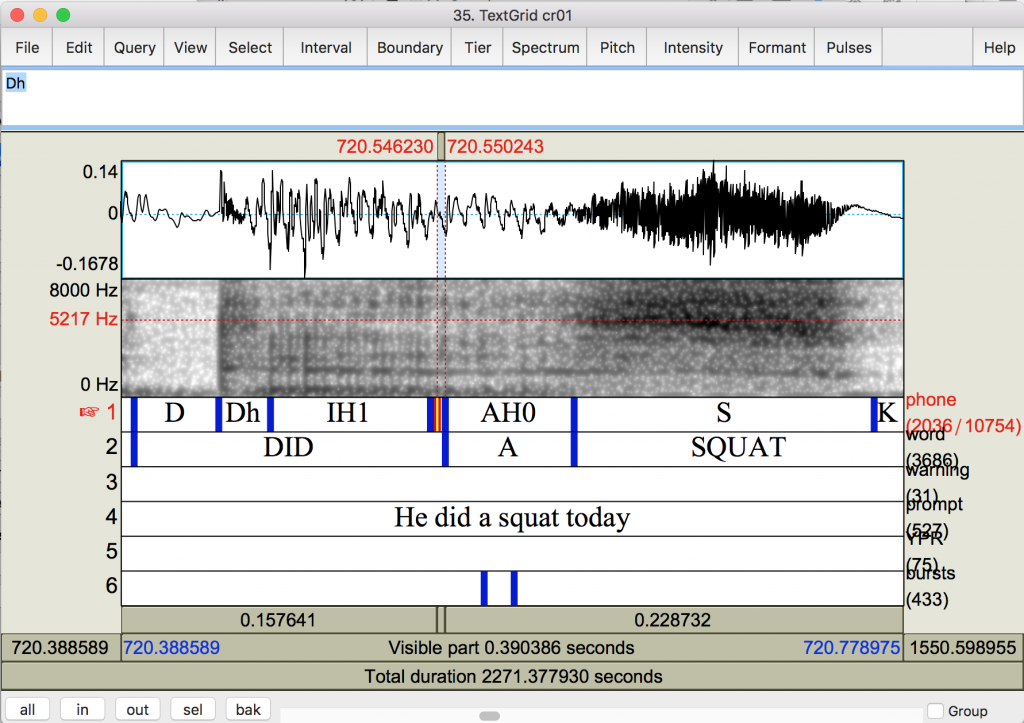

- For our purposes, we are segmenting stops and affricates in two parts, a closure (PTKBDG), and a release (Ph Th Kh Bh Dh Gh SH ZH). The closure may or may not have some voicing, but ideally, it should not include formants. Voiced stops will often have very short release intervals, and will need to be hand corrected.

- But sometimes there are traces of formants in a leaky closure, and that is ok.

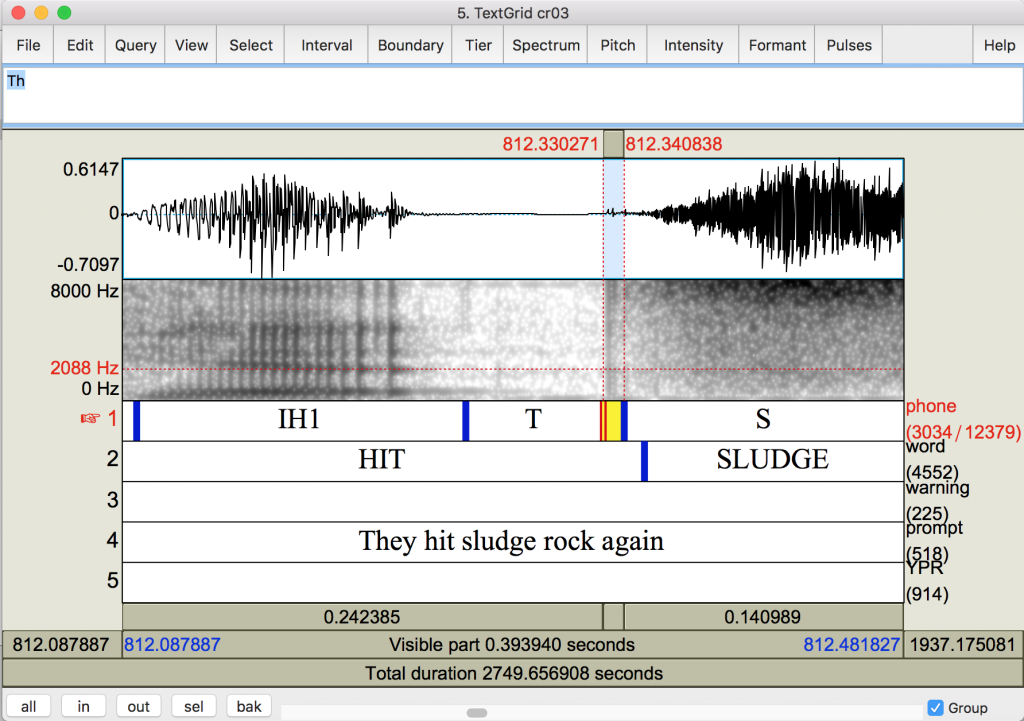

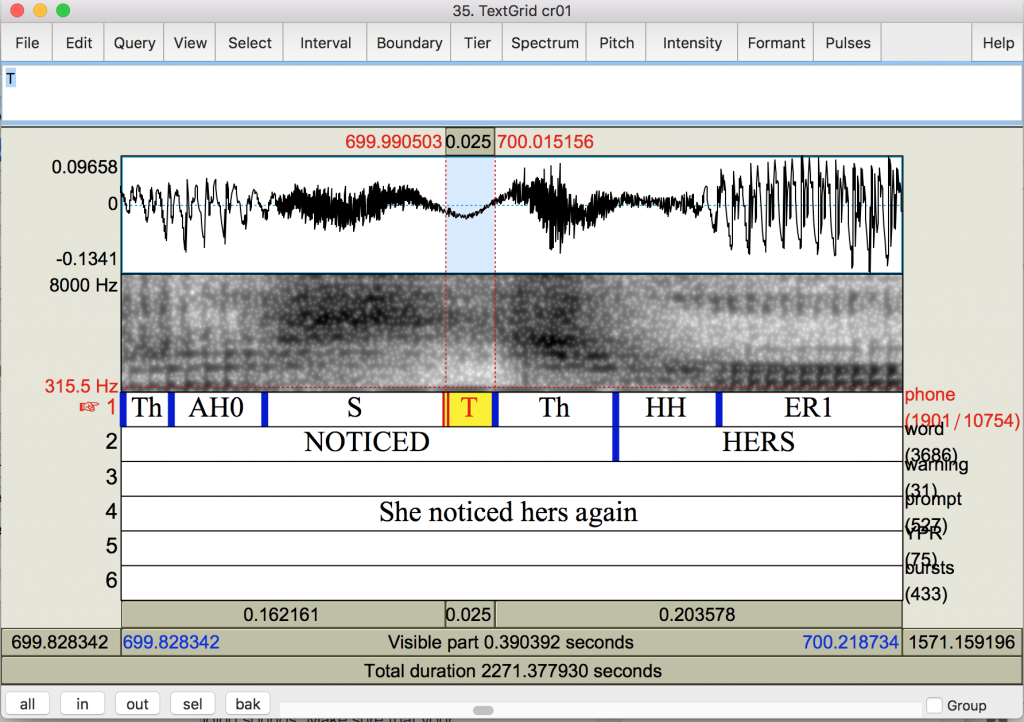

- The release interval starts at the burst or onset of frication, and ends at the onset of voicing or offset of aspiration/frication (or in the middle of these two when overlapping). Use the waveform to segment the release when possibe.

- If the stop release is followed by a fricative, watch for the change from burst to frication in the spectrogram.

(notice that this still needs to have the word boundary shifted to line up exactly with the boundary between T and S)

- Often the stop will be unreleased, in which case we just segment part of the closure as the closure and a small part as the release. If there are microbursts, these can be a good landmark for placing the release.

- If there is no closure, as in unstressed intervocalic /t/ or /d/, you should segment only a very small interval for the closure (since there isn’t actually a complete closure), and the remaining portion as the release.

Segment a tiny portion as closure (since there is no closure), and whatever is identifiable as the flap as the release.

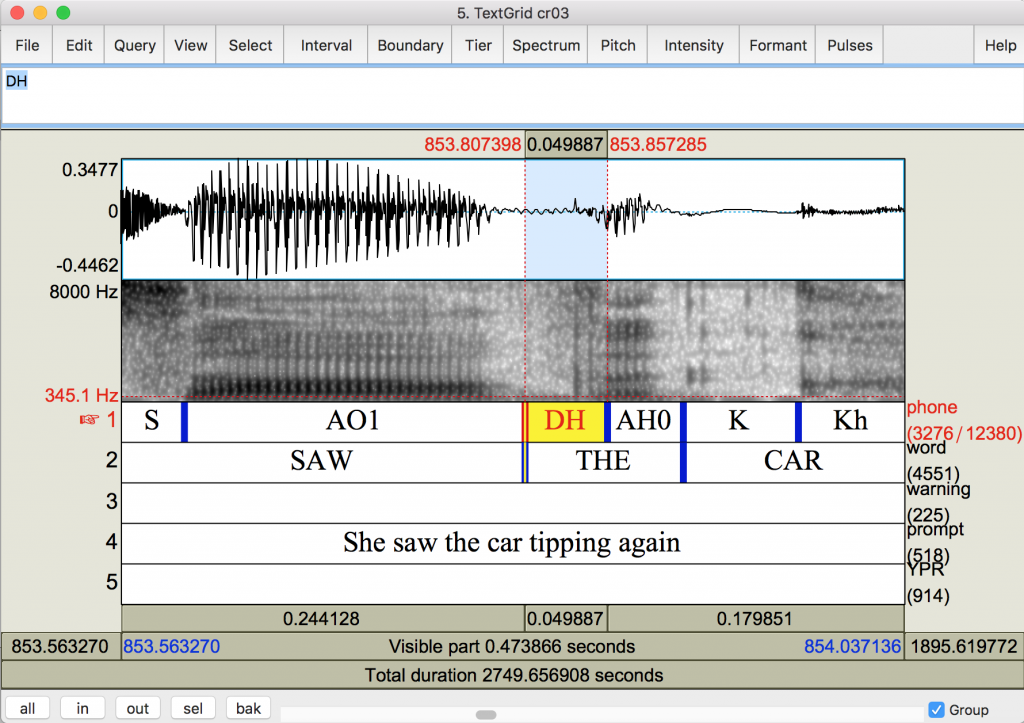

- Completely unreleased stops should have small intervals for the closure and very small intervals for the release following the offset of the vowel. This happens often with T followed by DH, where the closure (probably) switches to a dental articulation pretty quickly.

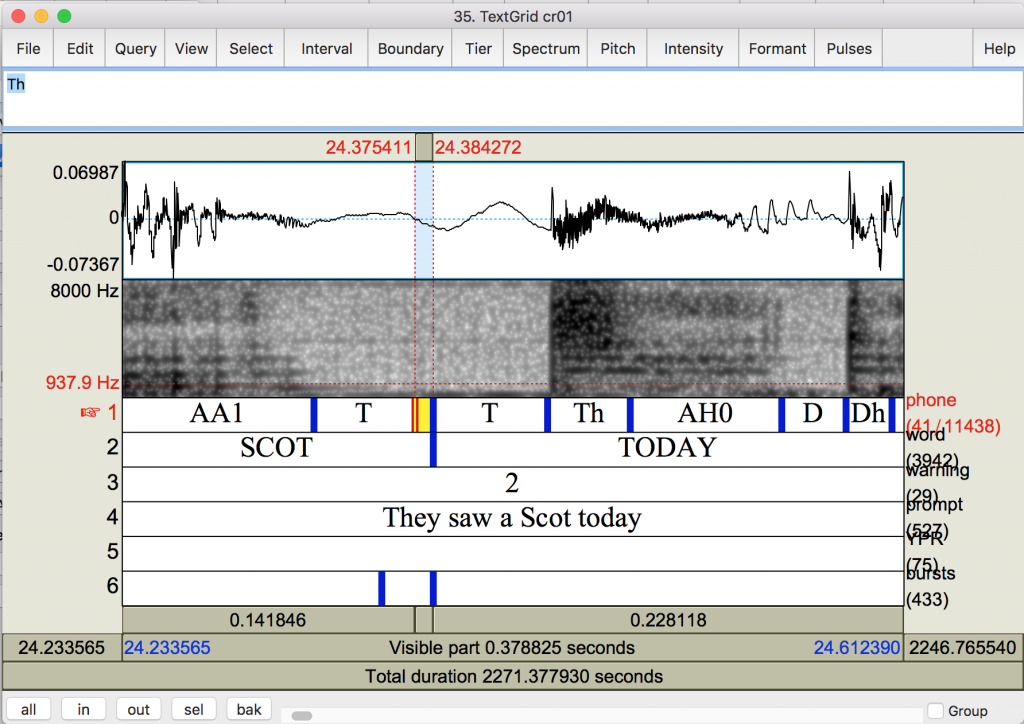

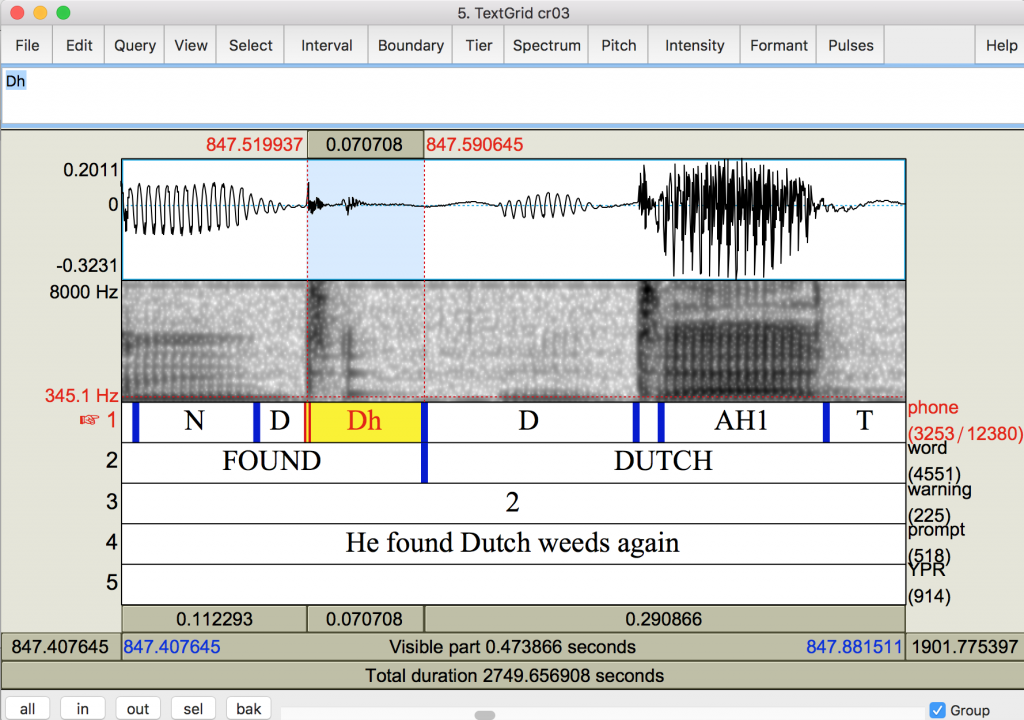

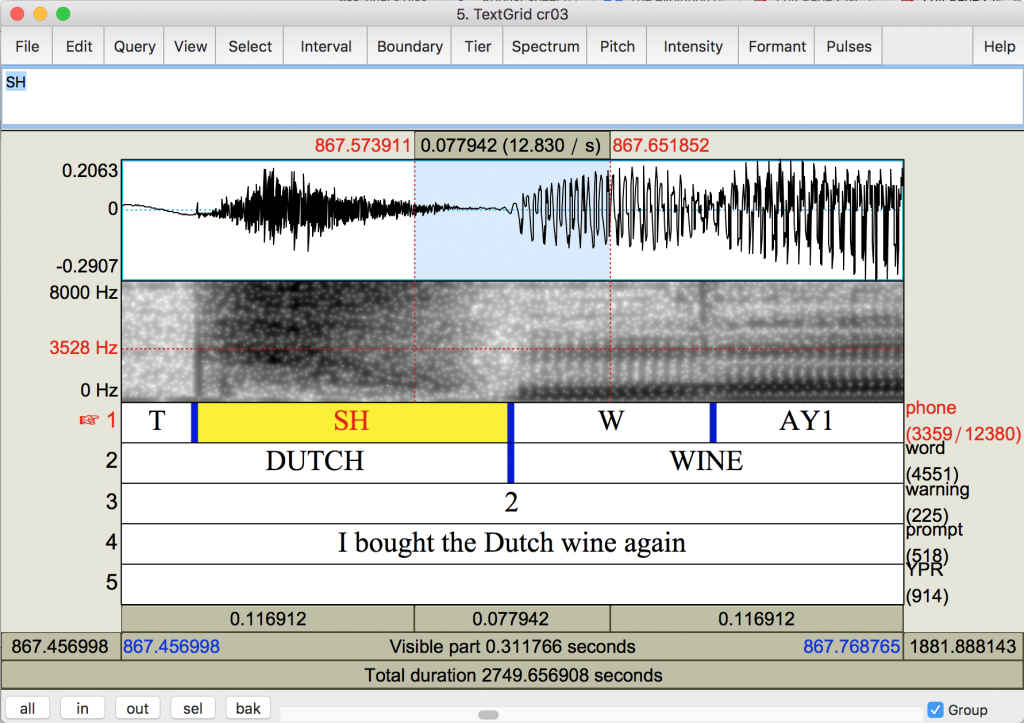

- If you have two stops next to each other with the same place of articulation (‘…found Dutch…’ or ‘…Scot today…’), there is likely to only be one stop closure and release, but we will segment it as if there were two. The important part to get right is the onset of the first closure and the last interval for the release. But we also want to maximize the amount of closure that is segmented as closure, so, if we are fibbing about a burst being there, make the burst interval be very small.

- And sometimes you get lucky, and there are actually two complete stops

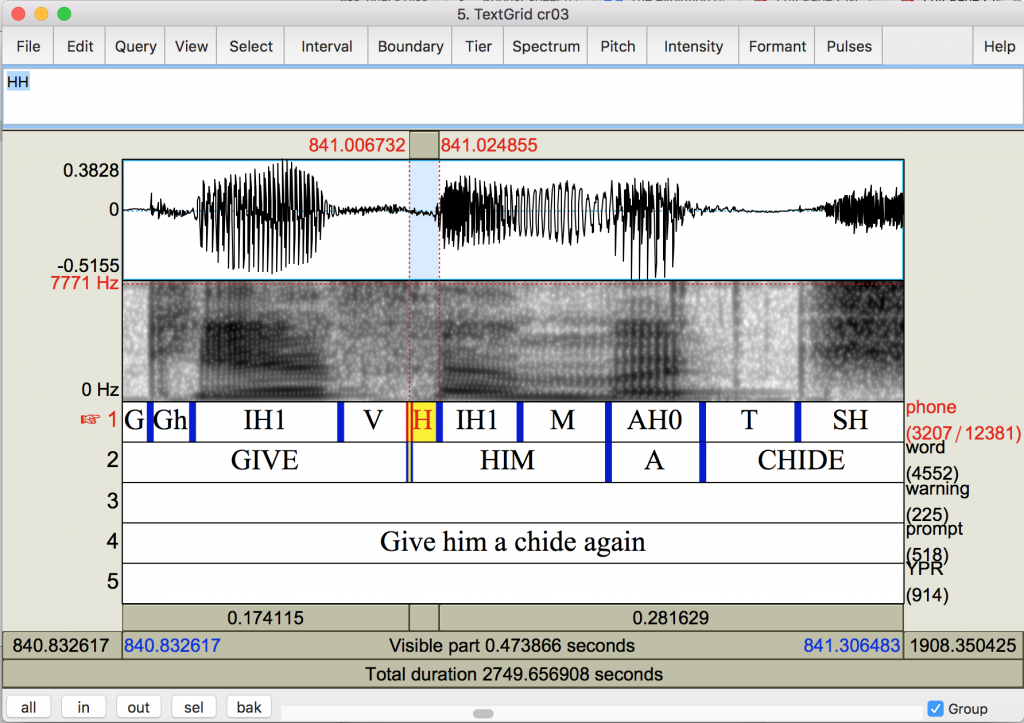

- Voiced stops are likely to have a very short release component, so you will have to hand correct to make sure the end of the interval doesn’t extend into the vowel, and the beginning lines up with the burst (leaving us with a very short release interval).

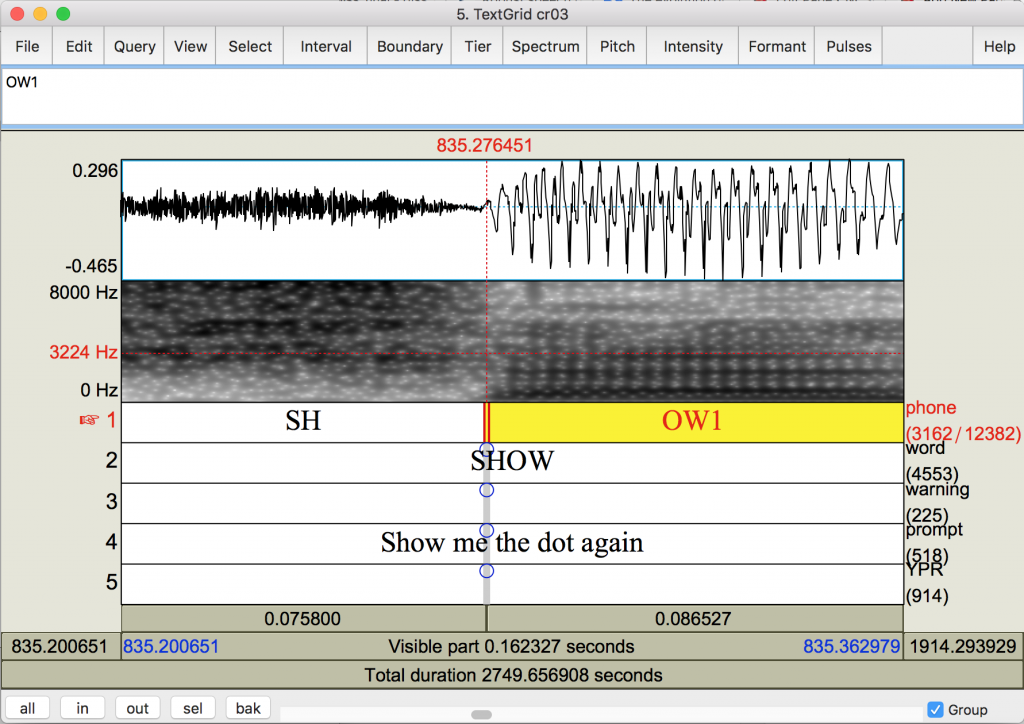

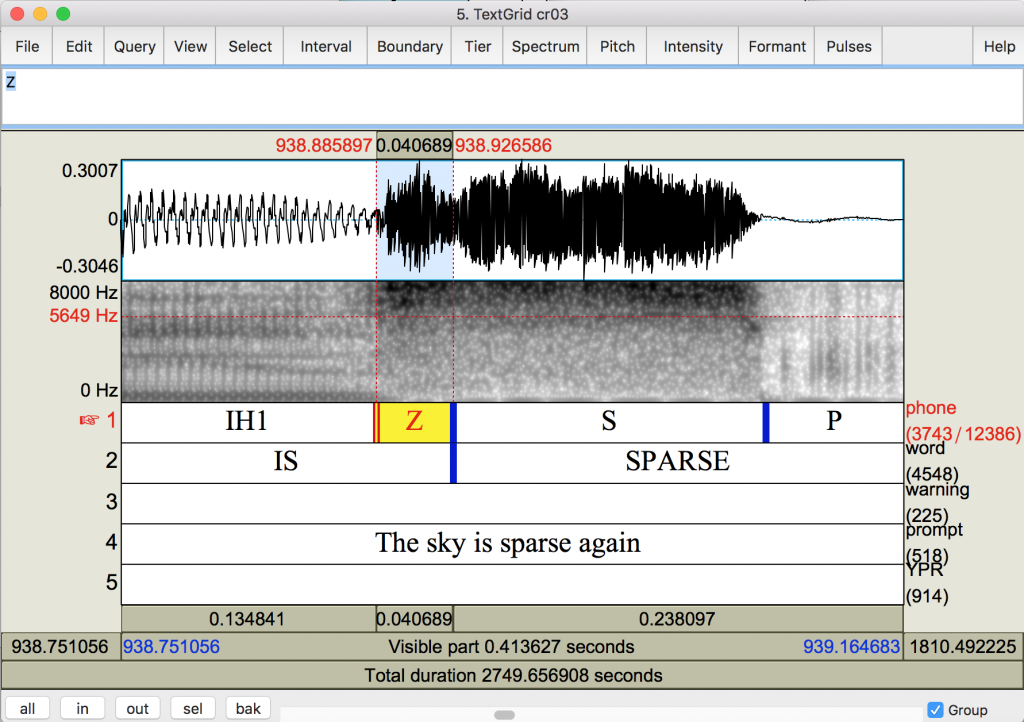

Fricatives

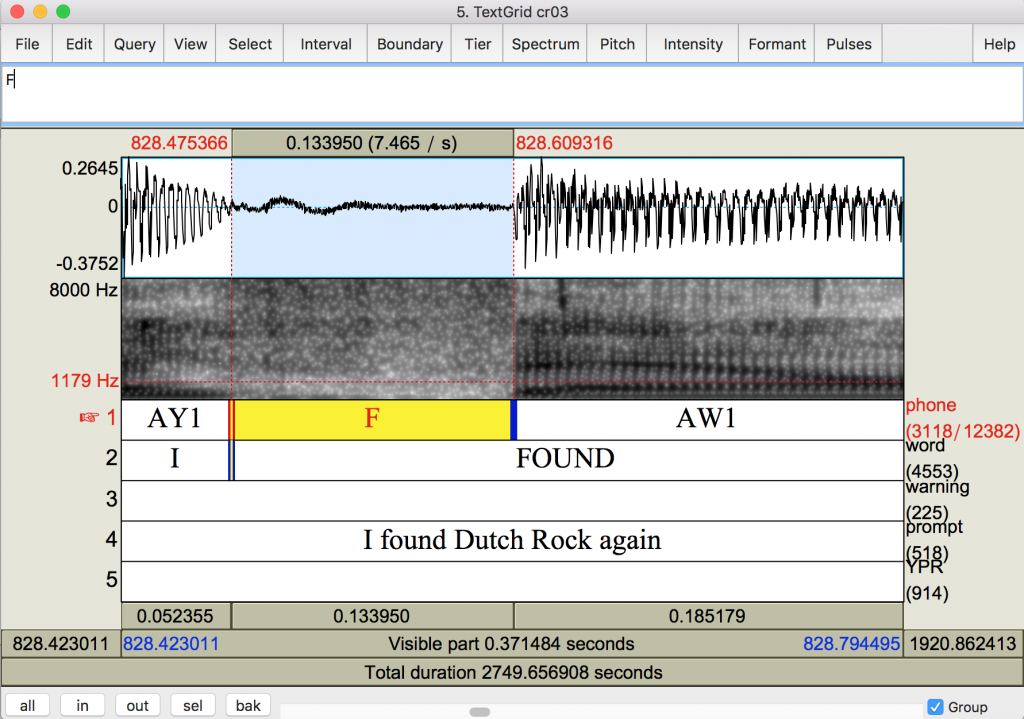

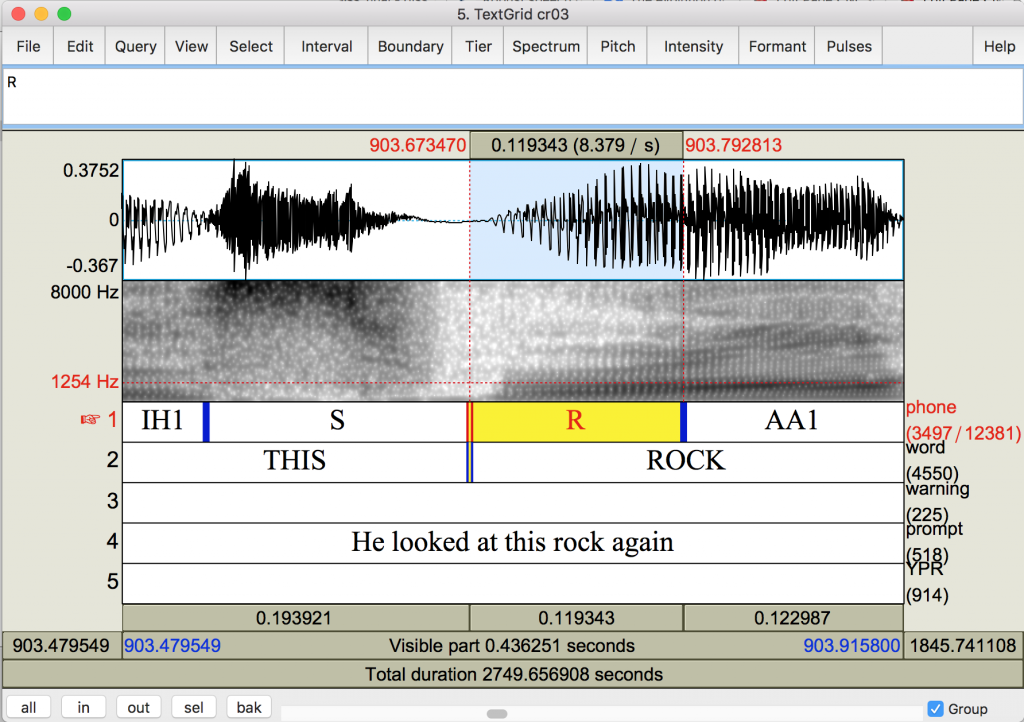

- Segment fricatives beginning at the onset of frication (where the waveform starts to look particularly fuzzy), and ending at the onset of voicing (first noticeable glottal pulse), unless frication carries over enough into the following segment to obscure any formants, then end at the onset of some formant structure.

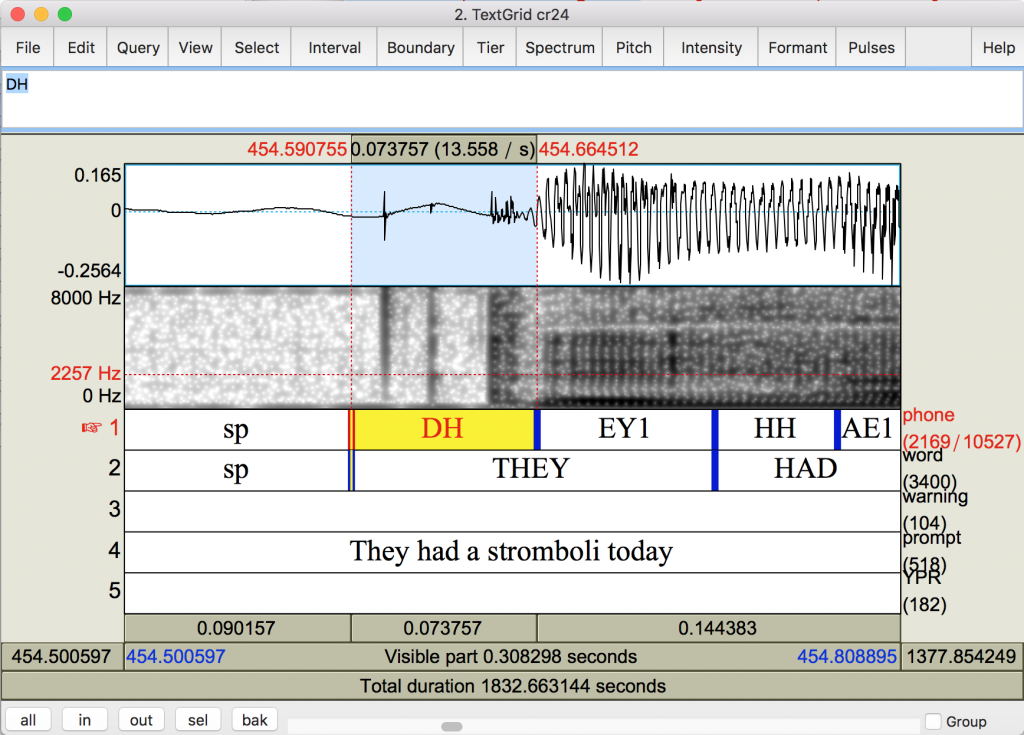

- Dental fricatives, especially phrase-initially, will often look like stops (or something else entirely). Just pretend that these are fricatives. Include some of the closure if it appears stop-like so that we can see the closure in the articulatory data.

- If two fricatives are next to each other, try to detect a discontinuity in the frication in the spectrogram. If all else fails, listen to the different components to determine a reasonable boundary.

Even if there is not a complete closure between a fricative and a stop (especially in /st/ or /str/ clusters), segment the quietest interval as the closure.

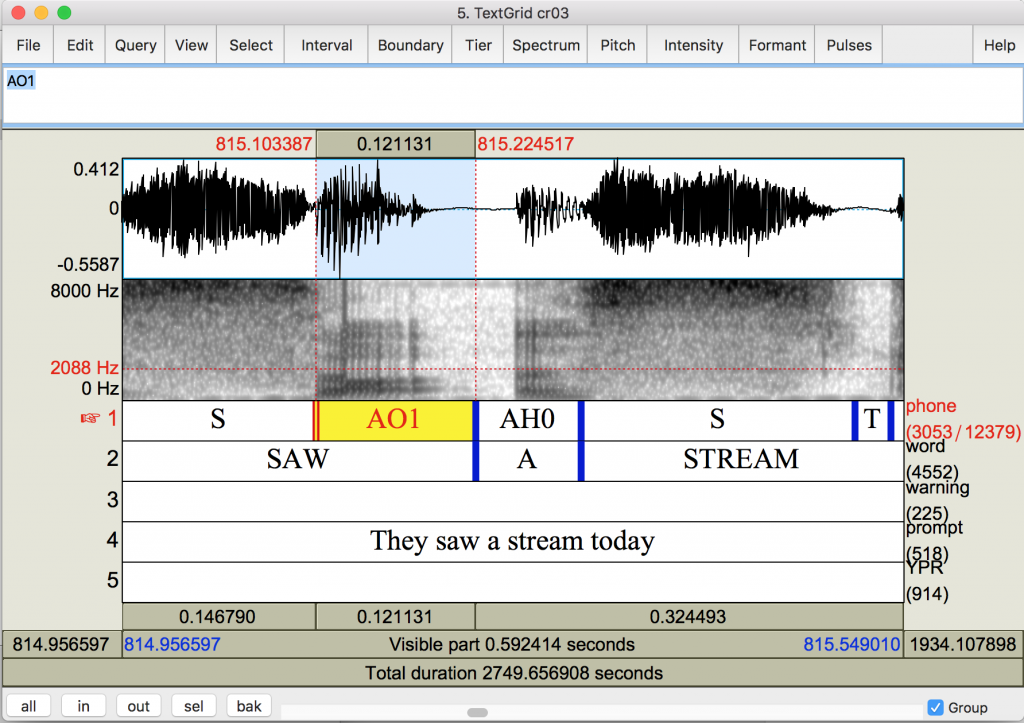

Vowels

- Vowels are very dynamic, with formant transitions on edges adjacent to consonants, and diphthongal changes in many vowels. The good thing is that stressed vowels are usually pretty clearly distinct from surrounding sounds. Make sure that your edges with obstruents (stops, fricatives, and affricates) are clean and crisp, as shown above. Where the vowel transitions from/into an approximant is more difficult, so see the section on approximants below.

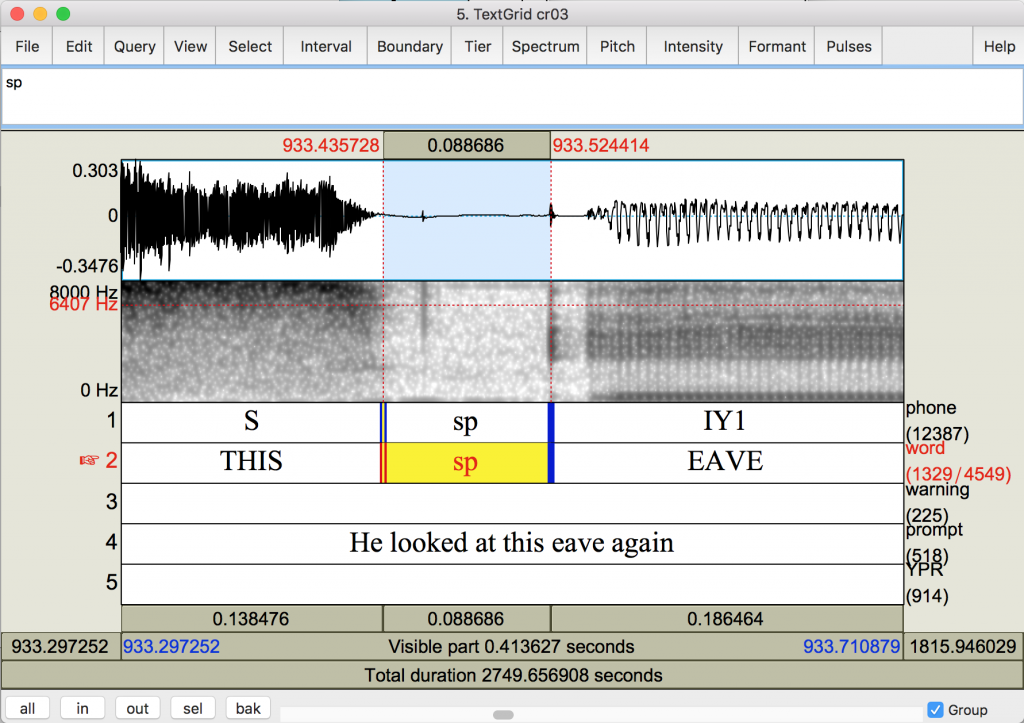

- When two vowels appear next to each other, they may have a short glottal stop separating them, or a longer sp (short pause), or they may just transition into each other with no separation. If the automatic segmentation has not inserted an sp, you can leave it, like this:

-

- You should only add a short pause separating two sounds if there is a prosodic break (a hesitation, pause, or unnatural separation of words in a phrase (think a ‘hot’ ‘dog’ as opposed to a ‘hotdog’)).

- If you (or the aligner) decide to add (or leave) an sp between two sounds, just make sure it is aligned with the end of one and beginning of the next.

Approximants

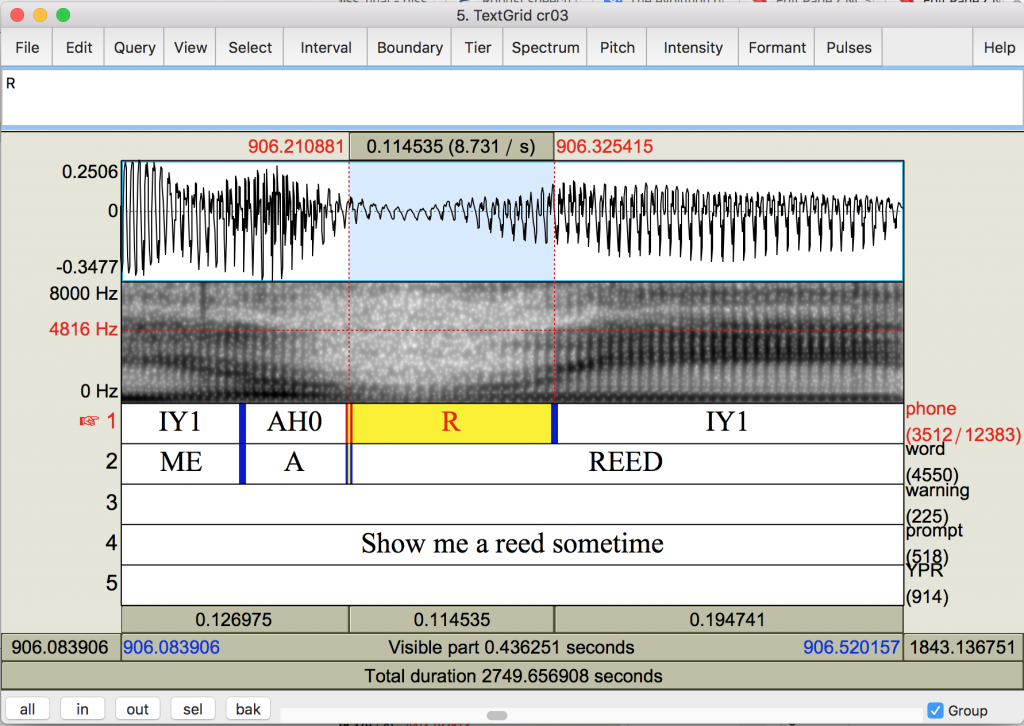

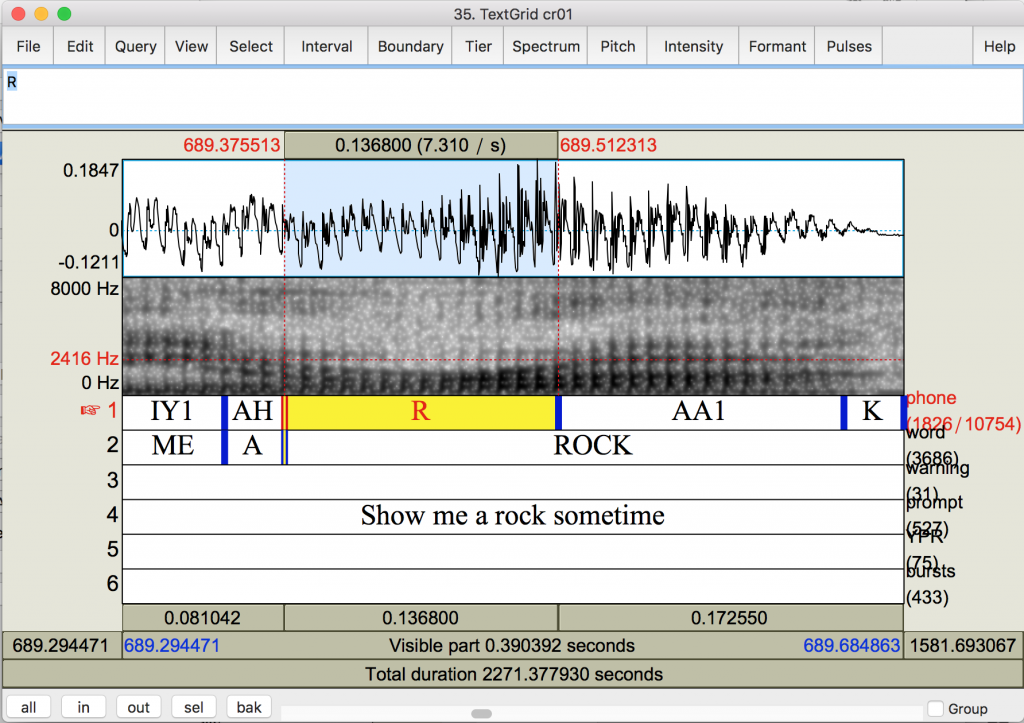

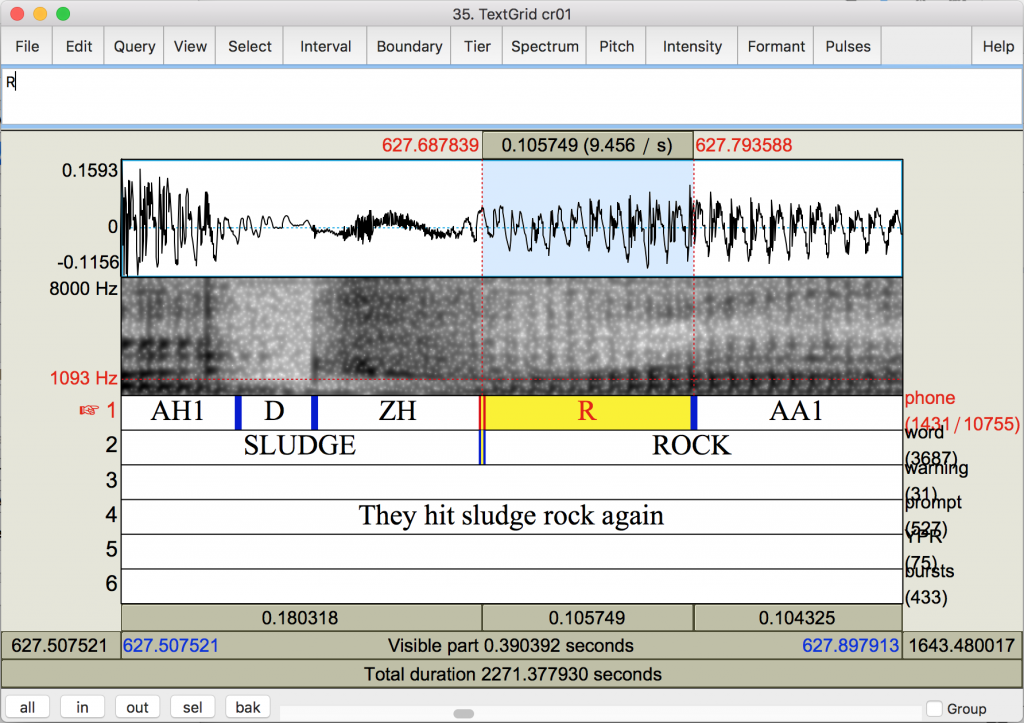

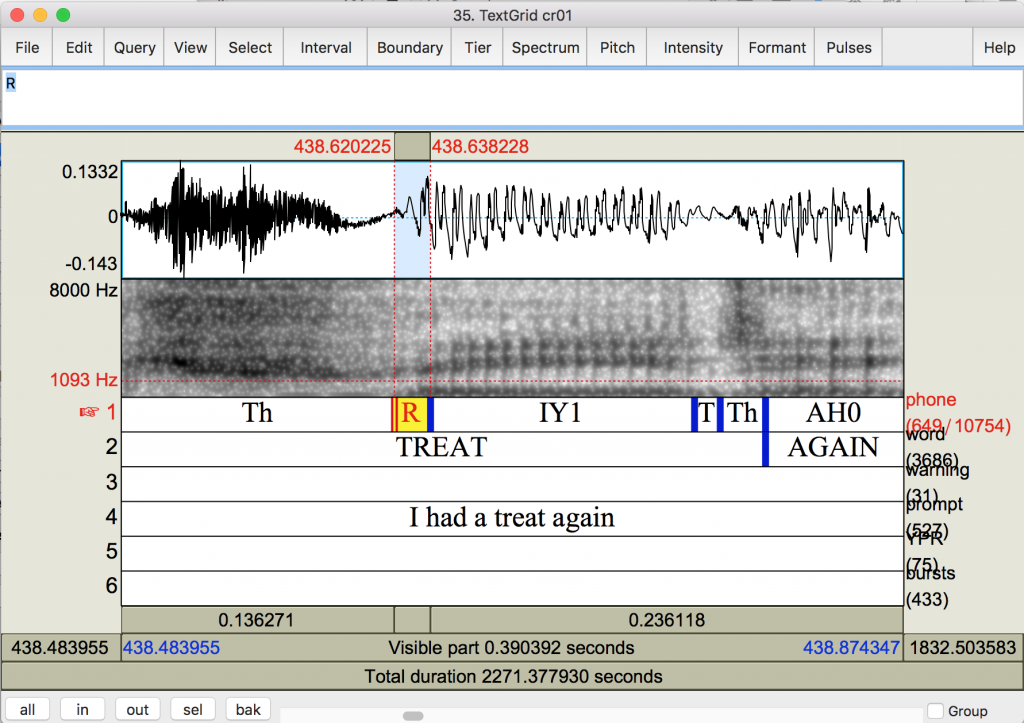

- /r/ is exemplified by a very low F2/F3 complex, lower amplitude than vowels, but sometimes has a little frication if it’s very consonantal. Try to capture some of the transition into a following vowel, as approximants are dynamic, but don’t take too much. Discontinuities (abrupt changes) in the spectrogram can be helpful in placing boundaries.

- /r/ preceded by a fricative may have a quiet interval between the end of the fricative and the onset of voicing, even though the articulators may be in position to begin the approximant. If the quiet interval is short, place the boundary in the middle, unless there is some cue that tells you where one thing stops or the next begins. (If it is an intentional pause, mark it as an sp.)

- Or /r/ might have its own frication. You should be able to hear the difference between a sibilant and a fricated /r/.

- In strongly coarticulated clusters, /r/ may be contained primarily, or even entirely within the frication. Just segment any portion of the segment that is a recognizable /r/, and if there is none, segment a small portion of the transition as the /r/.

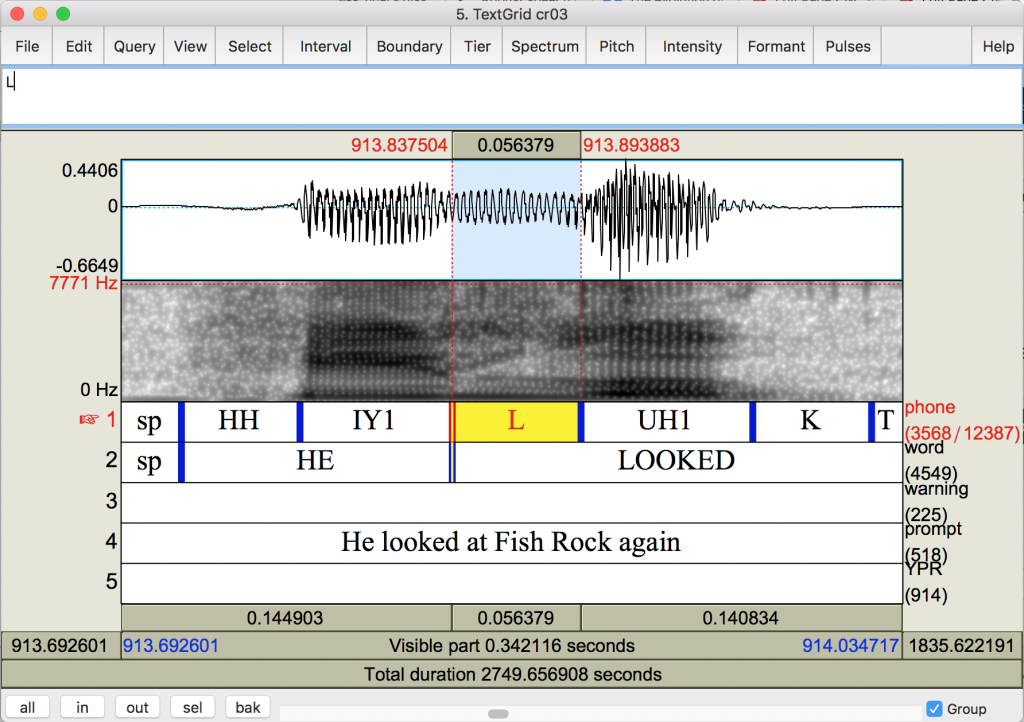

- /l/ has lowered F2, but high F3. As with all approximants, it should have lower amplitude than vowels, but it may have anti-resonances, which damp the sound further.

Look for discontinuities. /l/ may have damped resonances, and should have a lower amplitude relative to surrounding vowels

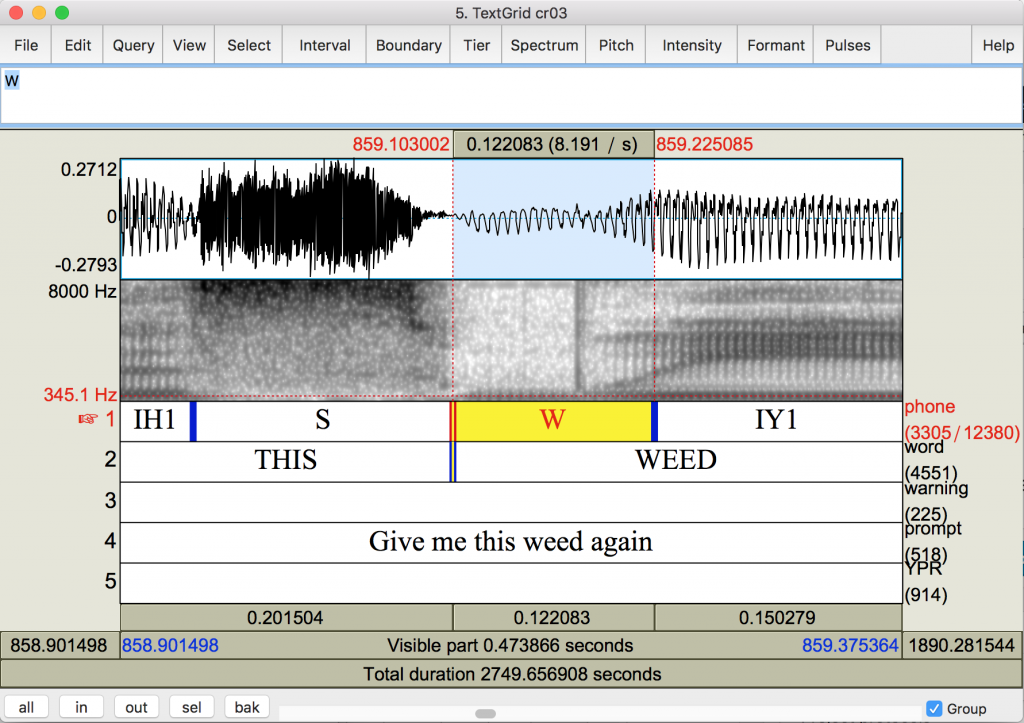

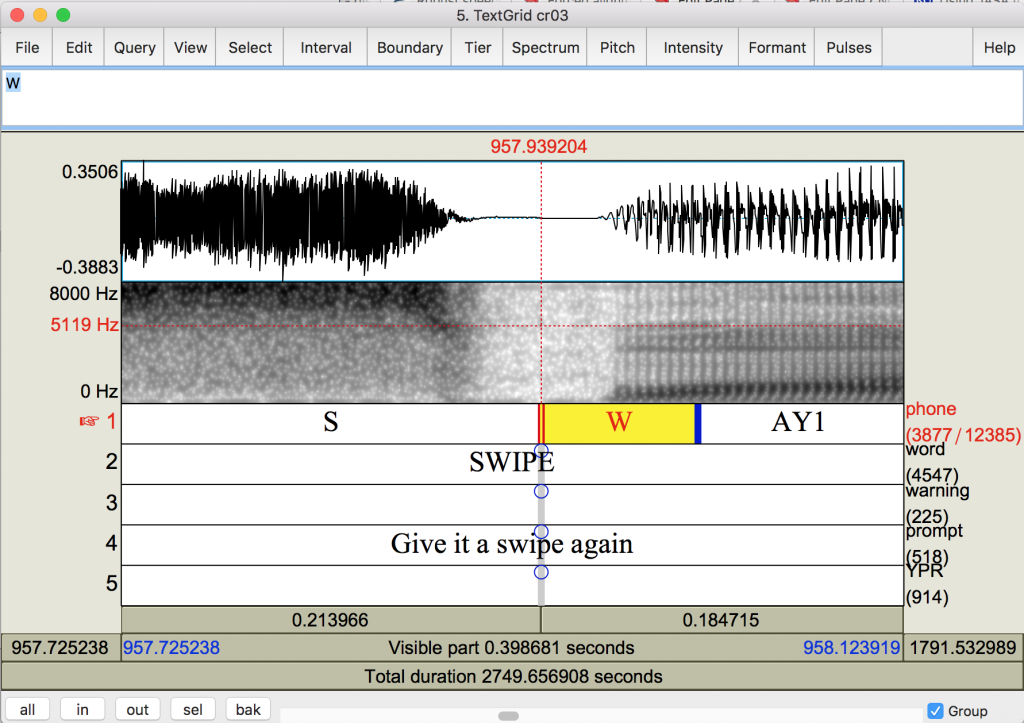

- /w/ also has a low F1/F2 complex, and reduced amplitude relative to vowels. It is dynamic. Mark the boundary between /w/ and a vowel about halfway through the formant transitions.